-

01Foreword

-

04Introduction

In Control Handbook

A Practical Guide for Civilian Experts Working in Crisis Management Missions

(5th edition)

Foreword

The EU faces a multitude of threats, both within and beyond Europe. We are witnessing a significant geopolitical realignment and escalating tensions worldwide. In this environment, the European Union's role as a global actor and our geopolitical awakening have become more necessary than ever.

EU Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) missions and operations are crucial instruments in our ambition for a stronger Europe in the world. Over the past two decades, they have been safeguarding Europe’s security by contributing to international stability and protecting EU interests and values globally.

As you are embarking on your new assignments in one of our missions or operations, I would like to extend my gratitude for your commitment and determination to contribute to a safer Europe and a more stable global order.

In recent years, the European Union has consolidated its position as a reliable global security provider. At present, over 5,000 dedicated women and men like you are working together under the EU flag in 23 civilian and military missions and operations across three continents. Together, they are promoting global security, responding to crises, and strengthening the capacities of partner countries.

We constantly strive to enhance the effectiveness of our operational engagement across the world, which is also one of the objectives of the EU’s Strategic Compass. To ensure the effectiveness of our missions, it is essential that we choose the right time to deploy the right people equipped with the right skills. Training is therefore of crucial importance.

I know that you, the women and men deployed in our CSDP missions and operations, are already experts in your respective fields, each having a professional career back home. Our training is tailored to help you adapt your expertise to the specific context of the various missions. As the global landscape evolves, so must our commitment to ensuring that our personnel are equipped with the highest level of targeted preparation.

This handbook will provide you with essential knowledge and tools to better cope with an evolving global environment and will be a vital resource during your deployment in the field. Many of you already bring a wealth of experience to your assignments, but each new environment poses unique challenges. This handbook is therefore concise and practical, and aims to help you in your daily tasks by addressing a broad range of real-life situations. For instance, how to navigate cultural sensitivities, understand human rights issues in diverse settings or provide the best advice and training to your local counterparts.

Your future assignment is at the core of our foreign policy, contributing to the common goal of protecting our Union and making it more resilient at home and abroad.

I thank you for your commitment and wish you success in all your endeavours.

JOSEP BORRELL

High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy/

Vice-President of the European Commission

Table of Contents

| Acknowledgments |

| Introduction |

| CHAPTER 1: Situating Yourself within the Crisis Management Framework |

| A. Explaining terminology and contexts |

| 1. EU crisis management |

| 2. UN peace and security operations |

| B. Top ‘Internationals’ in crisis management |

| 1. The European Union (EU) |

| 2. UN peace and security operations |

| 3. The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) |

| 4. The African Union (AU) |

| 5. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) |

| C. How are missions established? |

| 1. Mission mandates |

| 2. Mission setup: The EU way |

| 3. Mission setup: The UN way |

| D. Cooperation and coordination approaches |

| 1. The European Union’s comprehensive approach (CA) and integrated approach (IA) |

| 2. UN Policy on Integrated Assessment and Planning |

| 3. The UN cluster approach |

| CHAPTER 2: Policies, Thematic Issues and Guiding Principles |

| 1. Human security |

| 2. Human rights |

| 3. International Humanitarian Law (IHL) |

| 4. Protection of Civilians (PoC) |

| 5. Children and Armed Conflict (CAAC) and child protection |

| 6. Preventing Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (SEA) |

| 7. Gender equality and Women, Peace and Security (WPS) |

| 8. Refugees, IDPs, migrants and stateless people |

| 9. Environment, climate security and environmental peacebuilding |

| 10. Do No Harm |

| 11. Local ownership |

| 12. Good governance and anti-corruption |

| 13. Rule of Law (RoL) |

| 14. Security Sector Reform (SSR) |

| 15. Disarmament, Demobilisation and Reintegration (DDR) |

| 16. Policing tasks in peace operations and civilian crisis management |

| 17. Monitoring, Mentoring and Advising (MMA) |

| 18. Mediation, negotiation and dialogue |

| 19. Digital communications |

| CHAPTER 3: Preparing for Deployment |

| A. Understanding the situation |

| 1. Where are you going? |

| 2. Why are you going there? |

| B. What should you do before departure? |

| 1. Domestic arrangements |

| 2. Medical arrangements |

| 3. Professional arrangements |

| C. What should you pack before departure? |

| 1. Documents and related items |

| 2. Personal items |

| 3. Medical preparations |

| CHAPTER 4: How to Cope with Everyday Reality in the Field |

| A. Procedures and code of conduct |

| 1. Standard operating procedures (SOPs) |

| 2. Respect the code of conduct and ethical principles |

| B. Cultural sensitivity and diversity |

| 1. Respecting your host culture |

| 2. Trusting behaviours |

| C. Managing communication and media relations |

| 1. Personal communication |

| 2. Internal communication |

| 3. Crisis communication |

| 4. Media monitoring and rebuttals |

| D. Dress codes and uniforms |

| 1. Dress codes |

| 2. Recognising different uniforms |

| E. Addressing the language barrier |

| 1. Learning the local language |

| 2. Working with an interpreter |

| F. Go green. Be green |

| CHAPTER 5: Dealing with Health, Safety and Security Challenges |

| A. Staying healthy |

| 1. General health advice |

| 2. Hygiene |

| 3. Common illnesses: diarrhoea, fever and malaria |

| 4. Treating infections, parasites and bites |

| 5. Dealing with climatic extremes |

| 6. Environmental risks and challenges |

| 7. Mental health and stress management |

| 8. Substance abuse |

| 9. First Aid |

| B. Staying safe |

| 1. Cyber security |

| 2. At your residence and during recreational time |

| 3. Fire safety |

| 4. On the road |

| 5. Individual protective gear |

| 6. Mine hazards |

| CHAPTER 6: Technical Considerations |

| A. Communications equipment |

| 1. Radio |

| 2. Mobile devices |

| 3. Satellite communications (SATCOM) |

| B. Map reading and navigation |

| 2. Map coordinates |

| 4. Global Positioning System (GPS) |

| 5. Route planning |

| 6. Spatial information sharing and open-source intelligence |

| 1. Four-wheel drive vehicles |

| 2. Vehicle checklist |

| 3. Armoured vehicles |

| 4. Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) |

| CHAPTER 7: Handover and Departure |

| A. Final in-country steps |

| 1. Handover |

| 2. Mission debrief |

| B. Returning home |

| 1. Medical checkup |

| 2. Reintegration: work and family |

| 3. Post-deployment stress |

| List of abbreviations |

| International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia |

| Bibliography |

| Annex |

Acknowledgements

The Handbook in front of you is a testament to numerous individuals and organisations' collective effort and dedication. In particular, the Secretariat of the European New Training Initiative (ENTRi) project, that was hosted by the Center for International Peace Operations (ZIF) in Germany. They have laid the foundation of this handbook in 2012 and deserve a special recognition. Since then, this handbook has surpassed expectations, taking on a life of its own, thanks to your continuous contributions and support, dear readers.

This edition of the InControl Handbook wouldn’t have been possible without the support of everyone at the Centre for European Perspective, who was coordinating this update, the European External Action Service Peace, Partnerships and Crisis Management Directorate, and the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, who contributed to the creation of the 5th edition.

Our sincere thanks go to the European Union Civilian Training Initiative (EUCTI) Consortium of eight European training institutions: the Austrian Centre for Peace, the Centre for European Perspective, the Clingendael Institute, the Crisis Management Centre Finland, the Egmont Institute, the Folke Bernadotte Academy, the Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna and the Center for International Peace Operations (ZIF). Their understanding of the booklet as an essential piece for every mission member has given the EUCTI Secretariat the energy to compile all the contributions and illustrations. We additionally want to thank the Slovenian Red Cross and Slovenian Police for their contributions and reviews.

Special thanks goes to all artists, creatives, designers, operators and language editors who helped bring this handbook to life with their invaluable services.

Last but not least, we would like to express our gratitude to the European Commission’s Service for Foreign Policy Instruments (FPI) for their constant guidance and support.

Introduction

Stash it in your backpack, jam it in your pocket, or save it to your mobile device: This handbook's mission-friendly size, tough exterior and, for those who prefer to store all their information on their phones, clean and readable design, can handle any adventure and stick with you through thick and thin!

Welcome to the 5th edition of the In Control Handbook, which aims to prepare civilian experts for the demanding and dynamic environment of international crisis management missions. Whether you are a seasoned professional or new to the field, this comprehensive source of knowledge is tailored to support you at every stage of your deployment.

Its seven chapters outline relevant concepts, introduce salient topics and provide guidance and tools for your daily life in the mission, no matter where you are stationed.

Chapter 1 will provide an in-depth look at the major players in the field and explain how missions and their mandates are formed, as well as the organisational structures supporting them. In Chapter 2, you will find an overview of 19 crucial topics and cross-cutting themes central to contemporary peacekeeping efforts, such as human security and human rights, environmental protection, protection of civilians, gender issues and digital communication.

A successful mission relies on preparation. That is why Chapter 3 will help you trace your steps before your deployment, and Chapter 4 will focus on practical solutions for coping with everyday reality in the field, including guidelines on cultural sensitivity and building trust with local counterparts.

Chapter 5 will help keep you healthy and safe, both physically and mentally. Chapter 6 will teach you how to navigate the local and mission environment with the necessary tools and technical knowledge. The last chapter, Chapter 7, will help you deal with your return from the mission environment and develop strategies for your reintegration.

The text in front of you is a concise and practical overview of what can be a very challenging reality in the field. Crisis management missions deal with increasing demands and the expansion of their mandates, asymmetric threats, geopolitical tensions, humanitarian crises, and natural disasters. Experts deployed to these missions must be flexible to respond quickly and adapt to new realities. This handbook, however imperfect, can help you guide your tailored decisions and make sense of the bigger picture if you let it.

The 5th edition of the In Control Handbook builds on the well-known ENTRi legacy and strives to follow its example. This edition is published by the European Union Civilian Training Initiative (EUCTI) project, which comprises eight European training institutions and is co-funded by the European Union. It aims to provide need-based and tailor-made training courses for civilian experts deployed to international (civilian) crisis management missions and peacekeeping operations. Additionally, it seeks to extend training opportunities and capacity-building workshops to countries that are not yet contributing personnel to EU CSDP missions.

Introduction

Stash it in your backpack, jam it in your pocket, or save it to your mobile device: This handbook's mission-friendly size, tough exterior and, for those who prefer to store all their information on their phones, clean and readable design, can handle any adventure and stick with you through thick and thin!

Welcome to the 5th edition of the In Control Handbook, which aims to prepare civilian experts for the demanding and dynamic environment of international crisis management missions. Whether you are a seasoned professional or new to the field, this comprehensive source of knowledge is tailored to support you at every stage of your deployment.

Its seven chapters outline relevant concepts, introduce salient topics and provide guidance and tools for your daily life in the mission, no matter where you are stationed.

Chapter 1 will provide an in-depth look at the major players in the field and explain how missions and their mandates are formed, as well as the organisational structures supporting them. In Chapter 2, you will find an overview of 19 crucial topics and cross-cutting themes central to contemporary peacekeeping efforts, such as human security and human rights, environmental protection, protection of civilians, gender issues and digital communication.

A successful mission relies on preparation. That is why Chapter 3 will help you trace your steps before your deployment, and Chapter 4 will focus on practical solutions for coping with everyday reality in the field, including guidelines on cultural sensitivity and building trust with local counterparts.

Chapter 5 will help keep you healthy and safe, both physically and mentally. Chapter 6 will teach you how to navigate the local and mission environment with the necessary tools and technical knowledge. The last chapter, Chapter 7, will help you deal with your return from the mission environment and develop strategies for your reintegration.

The text in front of you is a concise and practical overview of what can be a very challenging reality in the field. Crisis management missions deal with increasing demands and the expansion of their mandates, asymmetric threats, geopolitical tensions, humanitarian crises, and natural disasters. Experts deployed to these missions must be flexible to respond quickly and adapt to new realities. This handbook, however imperfect, can help you guide your tailored decisions and make sense of the bigger picture if you let it.

The 5th edition of the In Control Handbook builds on the well-known ENTRi legacy and strives to follow its example. This edition is published by the European Union Civilian Training Initiative (EUCTI) project, which comprises eight European training institutions and is co-funded by the European Union. It aims to provide need-based and tailor-made training courses for civilian experts deployed to international (civilian) crisis management missions and peacekeeping operations. Additionally, it seeks to extend training opportunities and capacity-building workshops to countries that are not yet contributing personnel to EU CSDP missions.

Chapter 01: Situating Yourself within the Crisis Management Framework

The work of ’internationals’ in post-conflict situations can be complex and confusing. You may find yourself wondering who is doing what, how, why and where. Therefore, the first step is to know what the role of your organisation is in this context, so that you may better understand your own role and circle of influence. Learning the context of your mission will allow you to identify the stakeholders you are to engage with. The common goal is peace and stability of your target country or region, but knowing about the different mandates, tasks, internal structures, organisational cultures as well as funding sources is the decisive enabling tool in your new role.

This chapter will guide you through the missions’ architecture, types of international missions and their implementing organisations. It will provide an overview of the players, their organisational bodies, procedures and cooperation mechanisms, as well as some of the prevailing focus areas of today’s missions.

A. Explaining terminology and contexts

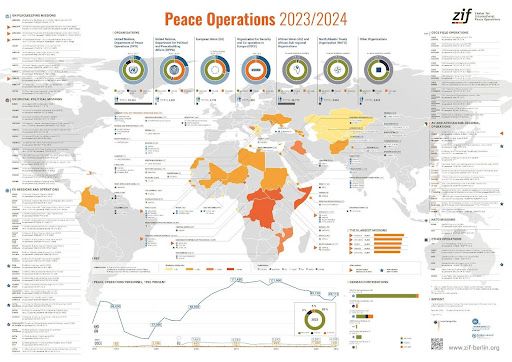

During 2023, there were over 75 missions worldwide, all different in their mandates, organisational structures and size. Since the first United Nations (UN) peacekeeping mission was established in 1948, crisis response has taken on many different forms. Therefore, you will encounter a variety of terminologies in this field of work. Namely, the terms describing missions have established themselves not only in relation to their mandates and functions but also depending on their respective implementing organisations. All organisations have their own jargon and may sometimes use different terms to refer to the same type of mission. Similarly, the same word may have different meanings depending on the context and organisation using it. For example, ‘protection’ means something different to humanitarian actors than it does to military peacekeepers.

Missions of the European Union (EU) are often referred to as ‘crisis management missions’, ‘Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP)’ missions or ‘EU operations’ (civilian missions and/or military operations). Other organisations use terms such as ‘peacekeeping missions’, ‘peace operations’ or ‘peace support operations (PSO)’.

This handbook consistently applies ‘peace operations’ and ‘crisis management missions’ as general terms while being as specific as possible when describing certain types of missions, such as monitoring or peace enforcement.

1. EU crisis management

The EU refers to crisis management as a general term, which includes various types of action. These may be mentoring, monitoring and advising (MMA) or capacity building in support of security and development, including training activities. EU crisis management is comprised mainly of crisis prevention measures and the deployment of crisis management missions. EU missions can have an executive mandate to act in place of local authorities for certain tasks.

Crisis prevention includes peacebuilding, conflict prevention, and mediation and dialogue. The EU can employ a wide array of external assistance instruments in support of conflict prevention and peacebuilding. Conflict prevention involves early warning, early identification of conflict risks, an enhanced understanding of conflict settings as well as the analysis of crisis response tools. On top of that, the EU can employ specific tools for identifying countries at risk of instability or violent conflict, such as the EU Conflict Early Warning System (EWS) and the Horizon Scanning. Mediation and dialogue push forward a political solution on the ground. In this context, the EU has developed its mediation support capacity, which ranges from high-level political mediation to facilitation and confidence building.

EU crisis management missions are deployed at the request of host countries or within a UN framework and can help in specific fields, such as monitoring borders or fighting piracy. EU crisis management missions support the rule of law (RoL) with a particular emphasis on police, border reforms and capacity building. The EU’s security sector reform (SSR) processes may support the implementation of agreements ending hostilities and sustaining peace. The EU has launched missions to offer strategic advice to host countries on reforming their civilian security sectors.

2. UN peace and security operations

Conflict prevention

Conflict prevention involves mediation and diplomatic measures to keep intra-state or inter-state tensions and disputes from escalating into violent conflict. It includes early warning, information gathering and a careful analysis of factors driving the conflict.

Conflict prevention by the UN may include the use of the Secretary General’s ‘good offices’, preventive deployment, confidence building, or mediation led by the UN Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs (DPPA). It may also include support with peace negotiations, assistance in the development of legislation, election monitoring, monitoring of agreements or capacity building, which could include coaching and training for civil society to stimulate non-violent conflict resolution at local or sub-regional levels.

Peacemaking

Peacemaking generally includes measures to address conflicts in progress and usually involves diplomatic action to bring hostile parties to a negotiated agreement. Peacemaking efforts may be carried out through the Secretary General’s “good offices” by envoys, governments, groups of states, regional organisations or the UN, as well as by unofficial or non-governmental management, judiciary, correctional services, customs or prominent personalities.

Peacekeeping

Traditional UN Peacekeeping Operations (e.g. UNTSO, UNMOGIP, MINURSO) are designed to stabilise and establish peace, however fragile, and to monitor that the agreements achieved by the peacemakers are being put into practice. Peacekeeping has mostly been assigned to UN (multidimensional) peace operations and includes a variety of multidimensional tasks, which help to establish the foundations for sustainable peace and may include a robust peacekeeping mandate to protect civilians. Modern peacekeeping missions often involve police, military and civilian actors who work in close collaboration with other UN institutions, such as the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) and the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA).

UN peacekeeping measures follow three guiding principles: consent of the parties, impartiality and the non-use of force, except in self-defence and defence of the mandate. The office of the UN Secretary-General may exercise its good offices to facilitate a conflict resolution. Furthermore, today’s multidimensional peacekeeping facilitates political processes, protection of civilians (PoC), disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration (DDR) of former combatants, election support, protection and promotion of human rights, and assistance in restoring the rule of law.

A distinction needs to be made between peace and security support operations. Whereas peace support operations are usually based on a peace or ceasefire agreement, security support operations can deploy police forces to restore the rule of law and stability in the country. A recent example is the establishment of the Multinational Security Support Mission in Haiti (authorised by the UN Security Council Resolution 2699), with the main focus on deploying police forces to establish law and order in Port-Au-Prince to hold elections.

Peace enforcement

Peace enforcement involves the use of a range of coercive measures and sanctions up to the point of military force when a breach of peace has occurred. It requires the explicit authorisation of the UN Security Council (UN SC). Its use, however, is politically controversial and remains a means of last resort. The enforcement of peace is regulated by Chapter VII of the UN Charter. For its authorisation, the UN SC must first determine a threat to international security, the existence of a breach of peace or an act of aggression according to Article 39 of the UN Charter. A legally binding resolution for all Member States (MS) requires the affirmative votes of nine out of the 15 UN SC members, including the affirmative votes of all five permanent members. It includes the long-term development and application of conflict transformation tools to prevent a relapse into violent conflict. It addresses issues that affect the functionality of state and society and enhances the capacity of states to effectively and legitimately carry out their core functions.

Multidimensional peace operations combine peacekeeping measures with peacebuilding elements. It requires coordinated action by international actors as well as the early participation of local parties. Peacebuilding activities are supported, for example, through programmes for SSR, stabilisation and recovery strategies, human rights, justice and corrections services, mine actions, and DDR. Many missions also provide support for the (re-) establishment of electoral processes.

- United Nations Peace Operations. “Manual. Police Mentoring, Monitoring and Advising in Peace Operations. New York. 2017. https://police.un.org/sites/default/files/sgf-manual-mma_2017.pdf

- Hunt, C. T., et al. (2024). UN Peace Operations and Human Rights: A Thematic Study. Center for Civilians in Conflict. Retrieved from https://civiliansinconflict.org/publications/research/report-un-peace-operations-and-human-rights/

- United Nations Peacekeeping. (n.d.). Terminology. United Nations. Retrieved May 21, 2024, from https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/terminology

- United Nations. (n.d.). Policy. Peacekeeping Resource Hub. Retrieved May 21, 2024, from https://peacekeepingresourcehub.un.org/en/policy

- United Nations. (2023). The Secretary-General's report on special political missions. United Nations Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs. https://dppa.un.org/sites/default/files/sg_report_on_spms_a-78-307.pdf

B. Top ‘Internationals’ in crisis management

Those major organisations, such as the UN, the EU, and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), vary significantly in nature, structure and organisational culture. They are living organisms that were created during a specific time in history and have evolved ever since. Member states’ political will and financial contributions as well as host states’ trust and consent form the mandates of the peacekeeping operations. In addition, the degree of organisational learning, capacity for managing change, types of personalities in senior management and flexibility of structures are all factors that influence the extent to which an organisation can adapt to changing environments. Similarly, these traits, as well as the nature of the organisation, play an important role in shaping the set-up and functioning of peace operations or crisis management missions.

This section will introduce the organisations and regional entities that you are most likely to encounter in the field and highlight the sub-divisions and bodies in charge of the planning and implementation of peace operations.

1. The European Union (EU)

The EU has long been engaged in crisis management, development cooperation and humanitarian aid. As part of the process of integrating states that are interested in admission into the Union, the EU employs instruments for stability and promotes measures for conflict resolution, reconciliation and democratisation. Since the establishment of the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) in 1993 and the European Security and Defence Policy (ESDP) in 1999 (renamed the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) with the Lisbon Treaty in 2009), the EU can apply military and non-military measures. The crucial strategic document for CFSP and CSDP is the EU Global Strategy (EUGS). Released 13 years after the release of the European Security Strategy (2003), it intends to guide the EU’s future activities in foreign affairs, defence, humanitarian aid, as well as trade or development cooperation. The EUGS, adopted by the European Council on 28 June 2016, has been followed by a set of guiding documents to help the EU operationalise its civilian and military interventions. The CSDP is thus one of many tools in the EU’s external relations toolbox. The CSDP – also referred to as ‘crisis management’ – allows the EU to deploy civilian, police and military personnel in missions and operations outside the EU, including joint disarmament operations, humanitarian aid and rescue operations, security sector reform, law enforcement, rule of law capacity building, military advice and assistance tasks, conflict prevention and peacekeeping, and tasks for combat forces in crisis management, which include peacemaking and post-conflict stabilisation.

Through an integrated approach, the CSDP strives to employ these measures in the earliest and most preventive way possible. The EU’s civilian and military instruments are clearly defined in the Treaty on the European Union (TEU). The EU is not autonomous in the use of these instruments but depends on the decision-making processes of its MS. The instruments are assigned to the European External Action Service (EEAS) under the direction of the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy and the Vice-President of the European Commission (HR/VP). The EEAS has organisational structures for the planning, conduct, supervision and evaluation of CSDP instruments. The EU MS decide about the use of all assets and resources they own in this field.

CSDP missions and operations have become a pivotal instrument of the EU’s CFSP. Since the first deployment in 2003, civilian CSDP missions have varied in scope (e.g. police, justice, security sector reform), nature (e.g. capacity building, training, executive tasks), geographic location and size. CSDP missions are always political tools and are conceived and controlled by the EU Member States through the Political and Security Committee (PSC), which exercises political control and strategic direction over CSDP missions.

Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP)

The Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) of the EU, established by the Maastricht Treaty in 1993, aims to preserve peace and strengthen international security in accordance with the principles of the UN Charter, to promote international cooperation and to develop and consolidate democracy and the rule of law, as well as respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms.

Member States of the EU define the principles and general guidelines for the CFSP. On this basis, the European Council adopts decisions or common approaches.

To make this handbook user-friendly and to enable the reader to quickly look up terms and actors, the following description of structures and actors does not reflect the actual hierarchy within the organisation but puts important instruments such as the Neighbourhood, Development and International Cooperation Instrument (NDICI – Global Europe) next to an institutional actor such as the Civilian Planning and Conduct Capability (CPCC), the headquarters for all civilian missions.

For a closer look at the planning processes, please consult Section C on the establishment of different missions.

Structures and actors involved in the CFSP include:

European Council

The heads of state or government of the 27 EU Member States meet four times a year in the European Council, which has become an institution in its own right with the implementation of the Lisbon Treaty. The High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy and the President of the Commission also attend these summits. The European Council plays an important role in defining the EU’s political priorities and direction. At these summits, the heads of state or government agree on the general orientation of European policy and make decisions about problems that have not been resolved at a lower level. The European Council’s decisions have great political weight because they indicate the wishes of the MS at the highest level.

Council of the European Union

The Council of the European Union is the EU’s decision-making body, in conjunction with the European Parliament (EP). It meets at the ministerial level in nine different configurations, depending on the subjects discussed. It has legislative, executive and budgetary powers. The Foreign Affairs Council, which discusses the CFSP and the CSDP, meets monthly, bringing together the ministers of foreign affairs. Since the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty, it has been chaired by the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, who is also Vice-President of the European Commission. Twice a year, and when needed, the ministers of defence are also invited. All the Council’s work is prepared or coordinated by the Committee of the Permanent Representatives of the Governments of the Member States to the European Union (COREPER).

European Parliament and national parliaments

The European Parliament (EP) is an important forum for political debate and decision-making at the EU level. The Members of the EP are directly elected by voters in all MS to represent people’s interests considering EU law-making and to make sure other EU institutions are working democratically.

The EP acts as a co-legislator, sharing with the Council of the European Union the power to adopt and amend legislative proposals and to decide on the EU budget. It also supervises the work of the European Commission (EC) and other EU bodies and cooperates with national parliaments of EU countries to get their input. The EP sees its role not only in promoting democratic decision-making in Europe but also in supporting the fight for democracy, freedom of speech and fair elections across the globe.

The Treaty of Lisbon set out for the first time the role of national parliaments within the EU. National parliaments can, for instance, scrutinise draft EU laws to see if they respect the principle of subsidiarity, participate in the revision of EU treaties, or take part in the evaluation of EU policies on freedom, security and justice.

High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy (HR/VP)

The High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy (HR), who is also Vice-President of the European Commission (VP), conducts the EU’s CFSP. The role of the HR/VP is to provide greater coherence in the CFSP as well as greater coordination between the various institutional players, particularly the Council and the EC. Furthermore, the HR/VP chairs the Foreign Affairs Council and exercises authority over the EEAS.

The European External Action Service (EEAS)

The European External Action Service (EEAS) was established to ensure the consistency and coordination of the EU’s external action. This service, at the disposal of the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy and Vice-President of the European Commission (HR/VP), is one of the major innovations of the Lisbon Treaty. Composed of officials from the services of the Council’s General Secretariat and of the Commission, as well as personnel seconded by national governments and diplomatic services, its task is to enable greater coherence in EU external action, including Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) missions, by providing the HR/VP with a whole range of instruments. The former delegations and offices of the European Commission became integral parts of the EEAS and represent the EU in about 140 countries around the world. EU delegations and CSDP missions have a growing need for close cooperation in countries where both are located. Cohesion creates added value and enhances the EU’s impact in the country and the region. The crisis management structures of the EEAS underwent reform and, in 2024, consist of the Managing Directorate for Peace, Security and Defence (MD-PSD) under the Deputy Secretary General for Peace, Security and Defence (DSG DEF), containing the Directorate for Peace, Partnerships and Crisis Management (PCM) and the Directorate for Security and Defence Policy (SECDEFPOL). In addition, there is the Civilian Planning and Conduct Capability (CPCC) and the European Union Military Staff (EUMS).

European Commission (EC)

The European Commission is the EU’s executive body and represents the interests of the European Union. It is fully involved in the work of the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP). It sits as an observer on the Political and Security Committee (PSC), as well as on various working groups, and it can issue proposals in this capacity, though it is not entitled to vote. It plays an important role in budgetary affairs since it implements the CFSP budget, allocated partly to civilian crisis management missions and to the European Union Special Representatives. Within the European Commission, the Service for Foreign Policy Instruments (FPI) is responsible for the operational and financial management of the budgets for the CFSP and the NDICI, as well as for the implementation of foreign policy regulatory instruments such as sanctions. Moreover, the European Commission supports crisis prevention and crisis management through its enlargement policy, development aid, humanitarian aid and neighbourhood policy.

The EU budget is based on a seven-year multiannual financial framework (MFF). The Commission proposal for the current MFF budget period that started in 2021 has significant increases for, among other things, internal security, defence and science.

Neighbourhood, Development and International Cooperation Instrument (NDICI – Global Europe)

The NDICI – Global Europe (NDICI-GE) is a new instrument merging several previous EU financing instruments, including the Instrument contributing to Stability and Peace (IcSP), which supported EU partner countries’ security and peacebuilding initiatives.

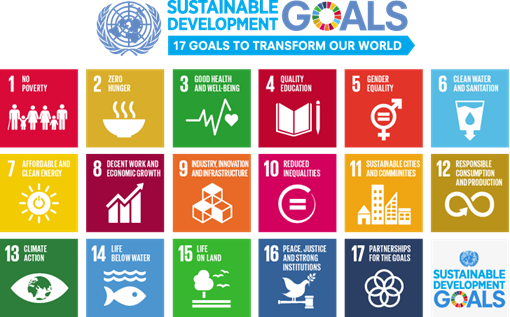

NDICI-GE enables the EU to support actions to promote peace, stability and conflict prevention through its 2021–2027 Peace, Stability and Conflict Prevention thematic programme, one of the four thematic programmes. The programme has two intervention areas: assistance for conflict prevention, peacebuilding and crisis preparedness and addressing global, trans-regional and emerging threats. Both areas complement actions under NDICI-GE geographic and rapid response pillars as well as the European Peace Facility’s activities in a multidimensional and conflict-sensitive way to contribute to the achievement of the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and Sustainable Development Goals.

The Peace, Stability and Conflict Prevention thematic programme serves as a tool to strengthen Europe’s role as a global leader by focusing on capacity-building measures for conflict prevention, peacebuilding and crisis preparedness. Additionally, it supports strengthening partnerships with other entities, such as international and regional organisations, public bodies, and civil society organisations, to jointly address global, trans-regional and emerging threats.

European Union Special Representatives

The European Union Special Representatives (EUSRs) support the work of the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy in troubled countries and regions. They play an important role in:

- Providing the EU with an active political presence in key countries and regions, acting as a ‘voice’ and ‘face’ for the EU and its policies;

- Developing a stronger and more effective EU Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP);

- Supporting the EU’s efforts to become a more effective and coherent actor on the world stage;

- Local political guidance.

The EUSRs are appointed by the Council based on recommendations by the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy.

Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP)

The Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) enables the EU to take a leading role in peacekeeping operations, conflict prevention and strengthening of international security.

Operational Range

The so-called Petersberg tasks describe the operational range of the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP). The original tasks were expanded and enshrined in the 2009 Treaty of Lisbon (TEU Art. 42) and include:

- Humanitarian aid and rescue operations;

- Conflict prevention and peacekeeping;

- Military crisis management tasks (e.g. peacemaking, joint disarmament operations, military advice and assistance, post-conflict stabilisation).

Financing and Recruitment

Two basic principles guide financing and recruitment. Civilian missions under the CSDP are financed by the CFSP budget, which covers personnel costs (e.g. per diems, other allowances for seconded staff, salaries for contracted staff), maintenance costs and assets. The costs of military CSDP operations are since 2021 financed through the so-called European Peace Facility (EPF) in part by the Member States participating in operations following the ‘costs lie where they fall’ principle and in part by all Member States through the EPF Operations pillar (=common costs).

Regarding the recruitment of personnel, the principle for both civilian and military CSDP missions and operations is that of secondment – staff are deployed by their national governments, which transfer their authority to the relevant missions and operations for the period of deployment. However, certain kinds of niche expertise (e.g. administration and finance, rule of law) are not readily available for secondment. Civilian CSDP missions, therefore, also have the option of employing international and local contracted staff.

Political and Military Structures

In order to enable the European Union to fully assume its responsibilities for crisis management, the European Council decided to establish permanent political and military structures in 2000, as outlined below.

The Political and Security Committee (PSC) meets two to three times a week at the ambassadorial level as a preparatory body for the Council of the EU. Its main functions are keeping track of the international situation and helping to define policies within the CFSP, including the CSDP. It prepares coherent EU responses to crises and exercises its political control and strategic direction.

The European Union Military Committee (EUMC) is the highest military body within the Council. It is composed of the Chiefs of Defence of the Member States, who are regularly represented by their permanent military representatives. It has a permanent chair selected by the Member States. The EUMC, supported by the EU Military Staff (EUMS), provides the PSC with advice and recommendations on all military matters within the EU. Its chair is the military adviser to the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy on all military matters and is the primary point of contact for operation and mission commanders of the EU’s military operations.

For advice on civilian crisis management, the PSC relies on the Committee for Civilian Aspects of Crisis Management (CIVCOM). This committee is the Council’s working group dealing with civilian aspects of crisis management; it receives direction from and reports to the PSC.

The PSC is assisted by the Politico-Military Working Group (PMG), and its meetings are prepared by the Nicolaidis Group. The Nicolaidis Group meets twice a week, always on the day before a PSC meeting, and Member States are represented by close associates of the PSC ambassadors.

Since the Treaty of Lisbon, these groups have been chaired by a representative of the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy or the European External Action Service (EEAS).

The Foreign Relations Counsellors Working Group (RELEX) or Foreign Relations Counsellors is a working group with horizontal responsibility for the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP). It is chaired by a ‘rotating presidency’. The presidency of the Council of the European Union is taken in turn by each Member State according to a rotation system for a period of six months. The order of rotation is determined unanimously by the Council of the EU based on the principle of alternating between ‘major’ and ‘minor’ Member States. The presidency ‘rotates’ on 1 January and 1 July each year. RELEX prepares all legal acts in the CFSP area and is, in particular, responsible for examining their legal, financial and institutional implications. It reports to the COREPER, which passes relevant documents for decision to the Council for approval.

Crisis Management Structures

The crisis management structures of the European External Action Service (EEAS) consist of the Managing Directorate for Peace, Security and Defence (MD-PSD), the Civilian Planning and Conduct Capability (CPCC) and the European Union Military Staff (EUMS), outlined below.

The MD-PSD consists of the Directorate for Peace, Partnerships and Crisis Management (PCM) and the Directorate for Security and Defence Policy (SECDEFPOL).

The Civilian Planning and Conduct Capability (CPCC) serves as the single-standing operations headquarters for all civilian CSDP missions. Each executive military operation is activated by an individual Member State-owned operational headquarters. Alternatively, the EU Operations Centre can be involved, or the EU can turn to NATO command structures under the Berlin-Plus agreements. However, military operations with a non-executive mandate, such as military training missions, operate under the command of the Military Planning and Conduct Capability (MPCC). MPCC, serving within the European Union Military Staff (EUMS), warrants cooperation and coordination between military and civilian actors through the Joint Support Coordination Cell (JSCC).

The Civilian Planning and Conduct Capability (CPCC) has a mandate to carry out the following activities:

- Plan and conduct CSDP civilian missions under the direction of the Political and Security Committee (PSC).

- Provide assistance and advice to the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy (HR/VP), the Presidency and the relevant EU Council bodies.

- Direct, coordinate, advise, support, supervise and review civilian CSDP missions.

The CPCC works in close cooperation with other crisis management structures within the EEAS and the European Commission.

The director of the CPCC, as the civilian operations commander, exercises command and control at the strategic level for the planning and conduct of all civilian crisis management missions under political control and strategic direction of the PSC and the overall authority of the HR/VP.

As the permanent Operational Headquarters (OHQ), the CPCC commands and controls all civilian CSDP missions and ensures the duty of care. It serves as a hub for information flowing from the field, coordinates between the missions and other EU actors in Brussels, and processes lessons from the complex mandates implemented in very difficult environments.

A substantial part of the CPCC’s work is also reporting to EU Member States on the outcome and impact of missions.

The European Union Military Staff (EUMS) comprises military experts seconded to the EEAS by Member States and officials of the EEAS. The EUMS is the source of military expertise within the EEAS. The EUMS works under the direction of the European Union Military Committee (EUMC) and Member States’ Chiefs of Defence, as well as under the direct authority of the HR/VP. The role of the EUMS is to provide early warning, situation assessment, strategic planning, communications and information systems, concept development, training and education, and support for partnerships. In concert with the EU Military Committee and EEAS partners, the EUMS creates the circumstances in which the military can conduct their operations and missions together with their civilian partners in the field.

The European Security and Defence College (ESDC) operates within the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP). Since its establishment in 2005, it is dedicated to providing training and education at European level and in the field of EU CSDP. The College complements national training efforts and ensures that civilian and military personnel from EU member states are well prepared for their deployment to EU CSDP missions and operations. Through its main activities – coordinating training courses, seminars, exercises and conferences – it promotes a shared understanding of best EU security and defence practices among the EU member states and globally.

Crisis Management Structures

In March 2024, there were 13 civilian missions, 10 military operations and one civilian-military mission. Altogether, 24 ongoing CSDP missions and operations consisting of around 4,000 EU military and civilian personnel. To date, the EU has conducted over 40 missions and operations under CSDP, including 25 civilian missions.

Civilian missions are supported and supervised by the CPCC in Europe, the Middle East and Africa, covering a large spectrum of tasks, including training, advising, mentoring and monitoring in the fields of police, rule-of-law (RoL) and security sector reform (SSR). EU Member States contribute to these missions with seconded national experts drawn mainly from the law enforcement and justice sectors.

Executive military operations are commanded and controlled by activated EU Operational Headquarters, while military operations with a non-executive mandate operate under EUMS – MPCC. Their spectrum of tasks includes operations at sea to counter piracy (e.g. off the coast of Somalia) or disrupt human smuggling and trafficking networks (e.g. the Mediterranean); providing capacity-building, training support or military assistance to armed forces (e.g. in Mali, Somalia, Central African Republic); and, if needed, creating a safe and secure environment (e.g. in Bosnia-Herzegovina). In future, Member States may appoint more joint civilian-military missions. The EU military mission in the Central African Republic, for example, has a civilian component.

As the EU Global Strategy has adapted in recent years to the changing security environment, the defence and military aspects of CSDP have been well developed. PESCO projects (Permanent Structured Cooperation in security and defence between Member States), contributing to the implementation of the Strategic Compass, are ongoing, and the new MFF suggests that EU funding for military capabilities will be regularly reviewed.

Important Documents

Strategic Compass for Security and Defence on 47 pages, approved by the Council of the EU in March 2022, establishes a common strategic vision for the EU’s security and defence. It emphasizes the need for resilient and reinforced civilian and military CSDP missions and operations. Furthermore, it reiterates the Member States’ commitment to strengthen the civilian CSDP by adopting a new version of the Civilian CSDP Compact, allowing for faster response to different types of crises.

The new Civilian CSDP Compact adopted on 22 May 2023 is a successor of the 2018 Compact and closely follows the premises determined in the 2022 Strategic Compass. It is essentially an agreement between the Member States, the European Council, the EEAS and the European Commission services, cementing their commitment to strengthen and enhance the effectiveness and capabilities of civilian CSDP missions. The set deadline for the full implementation of the Compact is in mid-2027. During the implementation process, Member States will need to update their national implementation plans (NIP), developed after the adoption of the 2018 Civilian CSDP Compact.

In December 2023, the Council of the EU approved the conclusion on civilian CSDP, underscoring the added value of civilian CSDP missions in the current geostrategic environment. It also welcomed the initiative to set up a Civilian Capability Development Process in 2024, emphasised training as a crucial element of capability development and endorsed the joint civilian-military approach to it, realised through the joint civilian-military CSDP Training Programme stemming from the 2022 revised Implemented Guidelines for the EU Policy on Training.

It is important to note that the EU CSDP Training Programme has a list of training courses on the Schoolmaster platform. The platform is used by diverse training providers to share training opportunities for both civilian and military CSDP.

2. UN peace and security operations

United Nations consists of three pillars: Human Rights and Humanitarian Issues, Sustainable Development and Peace and Security. For 75 years, UN peace and security operations have comprised various missions and interventions, employing more than two million uniformed and civilian personnel worldwide. The two most well-known are peacekeeping operations and special political missions, explained further in the text.

In 2023, the UN celebrated 75 years of peace operations with the slogan “Peace begins with me”. This year was also the year of A New Agenda for Peace, presented in July 2023 by Secretary-General António Guterres. The Agenda is the 9th Policy Brief of the 2021 UN Common Agenda that calls for reinforced multilateralism, global solidarity, sustainable development and enhanced forward thinking. The New Agenda for Peace outlines a strategic vision for strengthened multilateral peace and security efforts grounded in trust, solidarity and universality. It focuses on conflict prevention, regional approaches and heightened responsiveness to reflect the global (security) challenges and threats.

In the last decades, several key reform initiatives have shaped UN peace operations, as outlined below.

The Brahimi Report

In March 2000, the Secretary-General appointed the Panel on United Nations Peace Operations to assess the existing system’s shortcomings and to make specific and realistic recommendations for change. The panel was led by Lakhdar Brahimi, a senior Algerian United Nations diplomat, and was composed of individuals experienced in conflict prevention, peacekeeping and peacebuilding. The panel noted that to be effective, UN peacekeeping operations must be properly funded and equipped and must operate under clear, credible and achievable mandates. The Brahimi Report is seen as a crucial document of the reform of UN peace operations, proposing measures for more sustainable and effective UN peace actions.

High-level Independent Panel on Peace Operations

In October 2014, the Secretary-General appointed a High-Level Independent Panel on Peace Operations (HIPPO) to make a comprehensive assessment of the state of UN peace operations at present and the emerging needs of the future. This panel was the first to examine both peacekeeping operations and special political missions. The panel’s report was presented to the Secretary-General on 16 June 2015. Based on its analysis of weak spots in peace operations, the HIPPO report suggested four major shifts:

- The primacy of political solutions. Peace operations must be incorporated into a comprehensive political strategy, including solutions to achieve lasting peace.

- Spectrum of peace operations. The UN must be able to deploy its full spectrum of peace operations more flexibly and adapt quicker to changing conditions.

- Global and regional partnerships for peace and security. Stronger and more inclusive partnerships with regional and sub-regional organisations are needed.

- More field-focused UN Secretariat and more people-centred UN peace operations. Ensuring faster, more efficient and more effective peace operations will enable UN personnel in field missions to better serve the people they are mandated to assist.

In response, the Secretary-General presented his implementation report, The Future of United Nations Peace Operations. This report endorsed an action plan from the HIPPO report, focusing mainly on crisis prevention and mediation, UN cooperation with regional organisations, and the planning and implementation of peace operations.

Action for Peacekeeping

In 2018, the Secretary-General called for collective action through the Action for Peacekeeping (A4P) initiative. A4P aimed to refocus peacekeeping with realistic expectations, strengthen and secure peacekeeping missions, and mobilise greater support for political solutions and well-structured, well-equipped, and well-trained forces.

Consultations with Member States led to the Declaration of Shared Commitments on UN Peacekeeping, which features commitments in seven areas:

- Advance political solutions to conflict and enhance the political impact of peacekeeping.

- Strengthen the protection provided by peacekeeping operations.

- Improve the safety and security of peacekeepers.

- Support effective performance and accountability by all peacekeeping components.

- Strengthen the impact of peacekeeping on sustaining peace.

- Improve peacekeeping partnerships.

- Strengthen the conduct of peacekeeping operations and personnel.

On 1 January 2019, the peace and security pillar was restructured as part of a wider reform package launched by the Secretary-General. The overarching goals of peace and security reform were to prioritise conflict prevention and sustain peace, enhance the effectiveness and coherence of peacekeeping operations and special political missions, and move towards a single, integrated peace and security pillar. Furthermore, the reform aimed at aligning peace and security more closely with sustainable development, and human rights and humanitarian issues pillars to create greater cross-pillar coordination.

Peacekeeping operations

The first peace operation, the United Nations Truce Supervision Organization (UNTSO), was deployed in 1948. Since then, over 71 UN peacekeeping operations have been deployed worldwide—12 are currently ongoing. Peacekeeping is not an instrument foreseen in the UN Charter; it was developed in the 1950s out of necessity.

Over the 75 years of their existence, UN missions have evolved to meet the demands of different conflicts and a changing political and security landscape. Five types or ‘generations’ of peace missions can be distinguished: traditional peacekeeping, multidimensional peacekeeping, robust peacekeeping, missions with an executive mandate and, the most recent, regionalisation of peacekeeping missions with UN support. During the Cold War, traditional peacekeeping missions were the norm: lightly armed UN troops monitored the compliance of the conflict parties with peace agreements or ceasefires, in most cases after conflicts between state actors. These missions were based on the three principles: consent of the parties, impartiality and non-use of force except in self-defence. These missions remain pretty stable, especially compared to other robust PKOs and SPMs.

With the end of the Cold War, conflicts and threats have changed. Most conflicts now take place within states rather than between states, and many are asymmetric in nature. Peace missions have changed accordingly to address the domestic root causes of these conflicts and can now take on peacemaking and peacebuilding roles. Multidimensional peacekeeping missions, therefore, encompass many non-military tasks, such as disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration (DDR), security sector reform (SSR), rule of law support, protection of civilians, and human rights monitoring. In addition to military personnel, multidimensional operations also include police and civilian staff.

Since the 1990s, the UN has had to acknowledge that consent-based deployment of lightly armed peacekeepers is insufficient when peace agreements are not held or signed by all conflict parties. In response, the Security Council began to provide missions with so-called robust mandates, empowering them to use force not only for self-defence but also to enforce the mandate. Most current missions fall into this category of robust peacekeeping.

Another type of peacekeeping consists of a small number of missions with so-called executive mandates. In those cases, the UN performs state functions for a limited time, such as in Kosovo and East Timor. Recently, new generations of peacekeeping have brought the establishment of missions mandated by the UNSC, but implemented by multinational forces (as in Haiti) or African Union.

Special political missions

A significant part of the UN´s peace and security work in the field today is carried out by special political missions (SPMs). SPMs, which are primarily civilian, include offices of special envoys and advisers engaged in mediation and dialogue processes, groups of experts monitoring the implementation of Security Council sanctions regimes, regional offices conducting preventive diplomacy, and field missions accompanying complex political transitions and peace consolidation processes in countries such as Colombia, Iraq, Somalia, and Afghanistan.

Political missions have carried out good offices, conflict prevention, peacemaking and peacebuilding functions since the early days of the UN, even though these deployments have only been called ‘special political missions’ since the 1990s.

In its early days, the UN deployed a series of high-level mediators or other envoys, either upon request of the General Assembly or the Security Council or in the context of the Secretary-General’s good offices mandate. In the first 15 years of its existence, the UN also designed several field missions, including small political offices carrying out facilitation monitoring and reporting tasks and larger civilian presences to support political transitions, especially in the context of decolonisation and self-determination.

From the late 1960s until the end of the Cold War, the number of new missions mandated by either the General Assembly or the Security Council decreased. While Secretaries-General during this time continued to rely on special envoys and good offices missions, larger field-based civilian missions were rarely deployed.

Post-Cold War political transitions increased the demand for UN civilian support, particularly in areas such as electoral assistance, constitution-making, and the rule of law. From Central America to Africa, new missions were established to help Member States meet those demands.

Contemporary special political missions are deployed in a wide array of contexts, and the diversity of their structures and functions continues to increase. At the time of writing, there are 14 SPMs authorised by the Security Council or the General Assembly assisting in preventing and resolving conflict, coordinating international humanitarian and development aid, as well as helping Member States and parties to end conflict and build sustainable peace.

UN transitions

The UN peacekeeping operations' transition processes involve a strategic shift from peacekeeping to peacebuilding, aiming to ensure sustainable peace and stability in post-conflict regions. For instance, before its withdrawal at the end of 2023, the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) focused on transferring security responsibilities to local forces while supporting political and governance reforms. Similarly, the United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO) is gradually drawing down its military presence and enhancing its support for the Congolese government's capacity-building efforts before its scheduled withdrawal from the country by the end of 2024. In the Central African Republic, the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in the Central African Republic (MINUSCA) is prioritizing the consolidation of state authority and the disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration of former combatants.

Additionally, the planned transitions of Special Political Missions like the United Nations Assistance Mission for Iraq (UNAMI) and the United Nations Assistance Mission in Somalia (UNSOM) underscore a broader shift towards supporting political processes, electoral assistance, and the rule of law to foster long-term stability and development in these regions.

These transitions highlight the UN's adaptive strategies to address evolving on-the-ground realities and ensure a sustainable peacebuilding framework.

Main structures of the UN Peace and Security pillar

Department of Peace Operations

The Department of Peace Operations (DPO) serves as an integrated centre of excellence for UN peace operations, responsible for preventing, responding to and managing conflict and sustaining peace in the countries where peace operations under its mandate are deployed. This includes facilitating and implementing political agreements; providing integrated strategic, political, operational and management advice, direction and support to peace operations; developing political, security and integrated strategies; leading integrated analysis and planning of peace operations; and backstopping those operations. It consists of three main offices: the Office of Rule of Law and Security Institutions (OROLSI), the Office of Military Affairs and Policy, and the Evaluation and Training Division.

Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs

The Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs (DPPA) combines the strategic, political and operational responsibilities of the previous Department of Political Affairs (DPA) and the peacebuilding responsibilities of the Peacebuilding Support Office (PBSO). DPPA has global responsibility for political and peacebuilding issues and manages a spectrum of tools and engagements across the conflict continuum to ensure a holistic approach to conflict prevention and resolution, electoral assistance, peacebuilding and sustaining peace. It provides strategic, political, operational and management advice, direction and backstopping to all special political missions.

One of DPPA’s essential priorities is supporting the participation of women at all levels of peacemaking, conflict prevention and peacebuilding. The Women, Peace and Security is on the Security Council’s Agenda since 2000, with the adoption of Security Council Resolution 1325 on WPS. DPPA’s SPMs in the field include gender advisers or gender focal points providing internal advice and support. SPM’s external support includes promoting women’s direct participation through advocacy, consultancy, and mediation. Creating strategies for inclusive peace processes includes both internal and external support.

PBSO was founded to support the Peacebuilding Commission (PBC) by providing policy guidance and strategic advice. The PBSO assists the Secretary-General in coordinating the peacebuilding efforts of the different UN agencies. Furthermore, the PBSO administers the Peacebuilding Fund.

Peacebuilding Commission (PBC)

The Peacebuilding Commission was established by the UN Security Council and the UN General Assembly as an intergovernmental advisory body to assist countries in the aftermath of conflict. Its function is to lay the foundations for integrated strategies for post-conflict peacebuilding and recovery. The PBC brings together important actors, namely international donors, national governments, international financial institutions and troop-contributing countries to marshal resources. It provides recommendations and information on development, recovery and institution-building to ensure sustainable reconstruction in the post-conflict period.

Department of Operational Support

The Department of Operational Support (DOS) became operational on 1 January 2019 as part of the Secretary-General’s Management Reform. DOS provides logistical, administrative, technology, and other operational support to almost 100 Secretariat entities worldwide, which includes service delivery and integrated operational support for all peacekeeping operations and special political missions.

Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR)

The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), established in 1993 by the UN General Assembly, is primarily responsible for promoting and protecting human rights worldwide, assist governments, help empower people and mainstream human rights perspective into all UN programmes.

Ensuring respect and promotion of human rights in conflict and post-conflict settings is one of its integral goals. For example, many UN peacekeeping missions include a human rights component that is staffed by OHCHR personnel. Their role is to monitor and report on human rights abuses, provide technical assistance to local authorities, and engage in advocacy to promote human rights within the mission’s area of operation. Additionally, they develop strategies for the protection of civilians, especially vulnerable groups, provide training on human rights standards and practices and support efforts to strengthen rule of law and justice systems.

Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA)

OCHA is the part of the United Nations Secretariat responsible for bringing together humanitarian actors to ensure a coherent response to emergencies. OCHA also ensures there is a framework within which each actor can contribute to the overall response effect. OCHA’s mission is to:

- Mobilise and coordinate effective and principled humanitarian action in partnership with national and international actors to alleviate human suffering in disasters and emergencies.

- Advocate for the rights of people in need.

- Promote preparedness and prevention.

- Facilitate sustainable solutions.

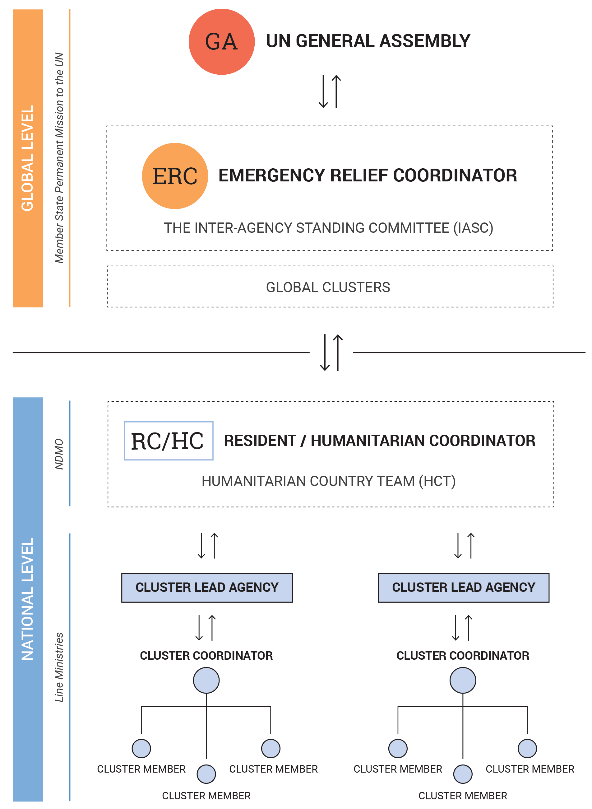

OCHA’s Civil-Military Coordination Section may coordinate the deployment of Military and Civil Defence Assets (MCDA) from several countries and multinational organisations. It is also responsible for devising the cluster approach, which will be covered in more detail in Section D of this chapter on ‘cooperation and coordination approaches’.

In support of the Joint Steering Committee chaired by the Deputy Secretary-General, OCHA and UNDP are advancing closer humanitarian and development collaboration by working towards collective outcomes over multiple years aimed at reducing need, risk and vulnerability at the country level.

UN Development Programme

As the United Nations' specialised agency focusing on development, the UN Development Programme (UNDP) has a mandate to support countries in their development path and coordinate the UN system at the country level. UNDP is also active in crisis prevention and recovery, aiming to support countries in managing conflict and disaster risks and rebuilding resilience once a crisis has passed. UNDP crisis recovery work acts as a bridge between humanitarian and longer-term development efforts. UNDP focuses on building skills and capacities in national institutions and communities.

3. The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE)

Encompassing 57 participating states from Europe, Central Asia, and North America, the OSCE is the world’s largest regional security organisation. Founded in the mid-1990s out of the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe (CSCE), the OSCE is characterised by its cooperative and comprehensive concept of security (stability, peace and democracy), which aims to improve the living conditions in its participating states.

The OSCE´s comprehensive security concept

Since 1990, the OSCE’s participating states have repeatedly affirmed their commitment to the organisation’s unique concept of comprehensive security. It comprises three dimensions:

- The politico-military dimension concerns matters such as military security, arms control, combating terrorism and human trafficking, and defence, security, and police reforms.

- The economic and environmental dimension promotes good governance, environmental awareness, corruption, economic development and the sustainable use of natural resources.

- The human dimension covers aspects such as respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms; establishment of democratic institutions; promotion of the rule of law; free, fair and transparent elections; media freedom; education; protection of national minorities; promotion of gender equality; youth participation; improvement of the living conditions and social participation of Roma and Sinti; and promotion of tolerance and non-discrimination.

Additionally, OSCE adopts a cross-dimensional approach, advancing a cooperative and a whole-of-society approach to tackling cross-border security challenges, such as radicalisation and violent extremism, organised crime, cybercrime, migration and climate change.

The OSCE’s functions and decision-making process

All participating states have equal rights and make decisions by consensus. The OSCE’s special status means that these decisions are politically but not legally binding.

Chairmanship, Secretary General, Secretariat and Institutions

The chairmanship rotates annually among OSCE’s participating states. It coordinates the decision-making process and determines the organisation's yearly priorities. The Chairperson-in-Office may appoint Personal or Special Representatives for particular issues, such as youth and gender issues. The Secretary-General, who heads the Secretariat in Vienna, supports the chairperson-in-office.

Important OSCE instruments are:

- Annual Security Review Conference;

- Forum for Security Co-operation;

- Economic and Environmental Forum;

- Human Dimension Implementation Meeting;

- Election observation.

In addition, three independent institutions help monitor the implementation of participating states' commitments and provide early warning: the Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights in Warsaw (ODIHR), the High Commissioner on National Minorities in The Hague, and the Representative on Freedom of the Media in Vienna.

OSCE field operations

In early 2024, the OSCE had 13 field operations in Southeast Europe, Eastern Europe, and Central Asia. A mission's deployment requires a decision made by the Permanent Council and an invitation by the host country. The mandates are tailor-made and generally aim to support the host country in fulfilling its OSCE obligations in all three dimensions, improving cooperation with the OSCE and enhancing local capacities. Some of the missions contribute to conflict prevention and early warning, while some include monitoring and reporting as part of their mandate. The first mission was deployed to Skopje in 1992 and is still active on the ground.

OSCE Conflict Prevention Centre (CPC) serves as a bridge between the field operation, the Secretariat and the Chairmanship, providing policy analysis and advice and coordinating OSCE field activities. The creation, planning, restructuring and closing of individual field operations fall under its jurisdiction.

4. The African Union (AU)

The African Union (AU) is an organisation consisting of 55 African states, with its headquarters in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. It was established on 9 July 2002 in Durban, South Africa, as a successor to the Organisation of African Unity (OAU).

The AU has been increasingly engaged in developing African peace and security actions on the continent. It seeks to promote development, combat poverty and maintain peace and security in Africa. For the maintenance of peace, security and stability, the African Peace and Security Architecture (APSA) was developed, which provides the AU Assembly of Heads of State and Government and its Peace and Security Council (PSC) with mechanisms through which to prevent, manage and resolve conflict situations on the African continent. Notably, the Constitutive Act of the African Union allows for the intervention of the Union in the affairs of its Member States under grave circumstances.

Since its inception in 2002, the AU has initiated almost 30 peace operations on the continent with the support of its regional partners, such as the Economic Community of West African States (ECPWAS) or the Southern African Development Community (SADC). In December 2023, following the UN Secretary-General's New Agenda for Peace, the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 2719, creating a framework for strengthened cooperation among the two organisations.

AU peace support operations

The African Union has worked since 2003 to develop the African Standby Force (ASF), a peace operations capability operated by the AU, the Regional Economic Communities and Regional Mechanisms (RECs/RMs) and Member States. Together with the PSC, the Early Warning System, the Panel of the Wise (PoW) and the Peace Fund, it forms the APSA.

Between 2004 and 2023, the AU deployed peace support operations in Burundi (AMIB), Sudan (AMIS), Comoros (AMISEC), Somalia (AMISOM), the Central African region (RCI-LRA), Mali (AFISMA), the Central African Republic (MISCA), and the Boko Haram-affected areas (MNJTF). The AU has also operated a peace support operation with the UN in Darfur (UNAMID). Current AU-led peace operations include missions in Somalia (ATMIS), Libya, Ethiopia (AU-MVCM), Sahel (MISAHEL) and Central Africa (MISAC).

The AU regularly undertakes conflict prevention missions (e.g. early warning, good offices, ad hoc committees), mediation missions (e.g. Panel of the Wise (PoW), good offices, mediation teams, high-level committees), and post-conflict reconstruction and development missions (e.g. African Solidarity Initiative and liaison offices in post-conflict countries). The AU has, in recent years, also undertaken regional security initiatives, such as in the Sahel (supporting the G5 Sahel joint force) and in Eastern Africa.

AU structures for peace and security

Peace and Security Council (PSC)

The Peace and Security Council (PSC) is comprised of 15 rotating members. It is charged with the maintenance of peace and security in Africa, making use of the APSA to engage in conflict prevention, management and resolution initiatives.

Political Affairs, Peace and Security Department (PAPS)